The Lit Sponge is written on the lands of the Wurundjeri people and acknowledges them as the traditional owners of this land, which was never ceded. I would also like to pay my respects to their Elders, past and present.

When I was 13, my best friend and I wrote a comic. And by ‘wrote a comic’ I mean she illustrated and wrote it and I, thinking it was a stroke of genius, shared it with all our friends. The titular character WYS NERO was a round, potato-like creature with giant circular eyes, eating a blue-pen rendered raw onion. Unfortunately, my friend is now a working professional who took down all the weird stuff we posted online in high school, but the moral (if there is one) – teenage girls do weird shit.

I can also remember the first time I visited a private school. In year twelve some friends and I went to see Carey Grammar School’s production of Chicago. My high school had just put on a direct-from-Savers run of Oklahoma and was now running a school-wide fundraising drive to raise money to buy a baby grand. But walking past the music department at Carey, looking in the windows, we counted four in white-walled, separate rooms. In that moment, I saw the monetary value that had been placed on private education … and knew that the same value had never been placed on mine.

It made me want to pick up some bulk-bought, lined Officeworks paper and a pen. Because again, teenage girls do weird shit. Why not do it for a cause?

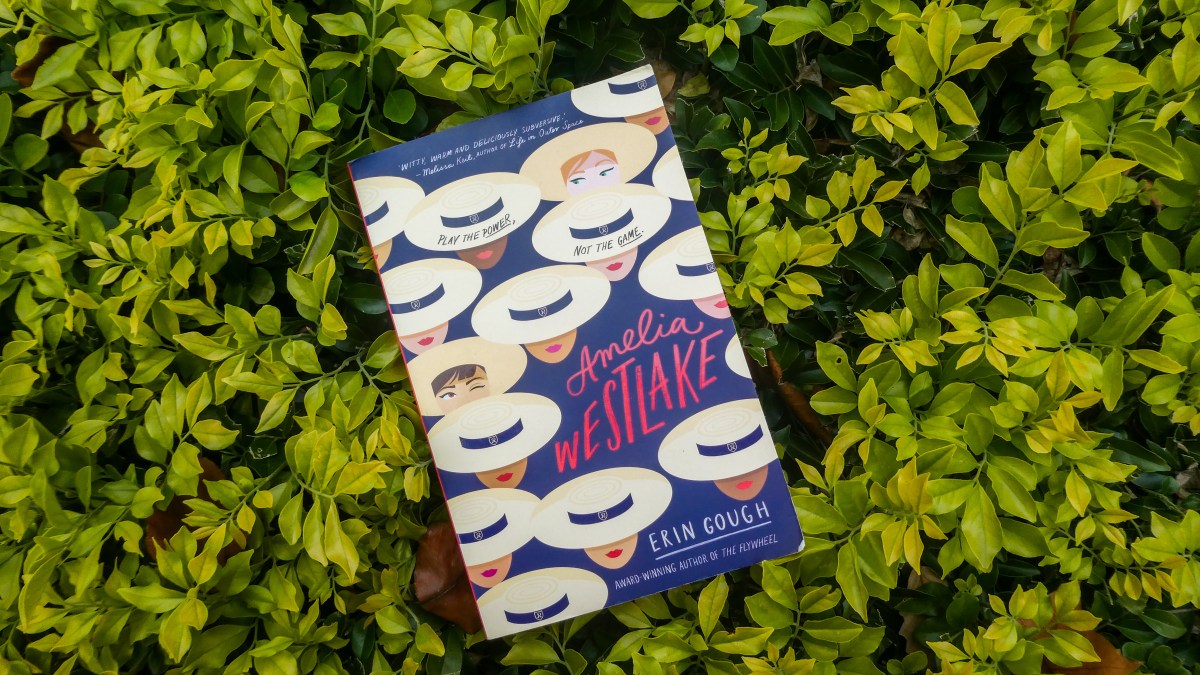

It’s somewhere in this vein that Erin Gough’s latest book Amelia Westlake comes in. It’s a member of a rising genre Alexa Wilson Kelly calls “Teen Girls Get Fed Up and Form Vigilante Girl Gangs to Knock Out Sexism at the Local Level”, centring on two girls tackling injustice at their school with an anonymous comic. The book’s primary-coloured, illustrated cover design of boater hats has a Madeline feel, and the story is thoroughly readable YA that tackles sexism, classism and homophobia in its opening chapters. It’s Will Grayson, Will Grayson, but with a bit more to say.

Unlike many other YA offerings, the heart of Amelia Westlake is female friendship, solidarity and a queer romance. Its relationships unfold with slow vulnerability, and allow the main characters Harriet and Will to move from the caricatures of teachers pet and misfit into a more complex understanding of each other and the world they’re fighting against. Gough treats her characters with authenticity and care, giving context to the clichéd identities high schools and social groups demand from young women. The everyday concerns of their school life become real, and as Will and Harriet gain nuance to the reader, they also gain nuance to each other. While Harriet’s overly-idealistic teacher’s pet is played-up in a way that some readers might struggle with, her slow willingness to put aside her absolute belief that the adults and friends in her life are well-meaning is one of the more captivating character progressions in this story. The two girls enable each other to rebel in meaningful ways, and Harriet’s rebellion is absolute.

Amelia Westlake starts with these small rebellions that quickly become a school-wide revolution. The girls are brought together by a shared feeling of injustice about their school’s sexist and predatory swimming teacher, Coach Hadley. An ex-Olympian, Hadley is a key part of Rosemead’s narrative around reputation and prestige, a power he uses to sexually harass and molest his students. As tension around Rosemead’s continued inaction builds, Will and Harriet are placed in a position all too familiar for many young women: unable to let a status quo of predatory behaviour continue and attempting to force change on an institution that has “conditioned us so completely that nobody even considers questioning what goes on here anymore.”

While Hadley isn’t the only injustice the girls fight, he is the centre point that the book revolves around, and a reminder that all too often, girls are exposed to sexism, homophobia and trauma at a young age. Amelia Westlake doesn’t shy away from this, and reading it carries with it some of the horror of seeing the violence of Larry Nassar through a teenage lens. The girls’ cartoon about Hadley is no revelation to their fellow students, it’s an acknowledgement of an open secret that takes place among plans for the school formal and VCE stress. Student reactions come with a mixture of solidarity and victim blaming, often tied to the characters relative privilege, but ultimately the book shows that real change, change that targets power and institutions, is led by young people – and often, young women. It also shows the personal cost of their bravery, and that the worst victims of sexual assault are often the least empowered to speak up. Taking action against these injustices – especially on behalf of those who are less able – is, as Will says, “what Amelia Westlake is all about.”

Amelia Westlake doesn’t shy away from these issues, and reading it carries with it some of the horror of seeing the violence of Larry Nassar through a teenage lens. The girls’ cartoon about Hadley is no revelation to their fellow students, it’s an acknowledgement of an open secret that takes place among plans for the school formal and VCE stress.

Gough’s second novel published through Hardie Grant Egmont is also a sign of changing attitudes. Its win of Readings’ Young Adult Prize for 2018 and position as a CBCA notable is an overall win for Australian-born YA, and its recent shortlisting for the Golden Inky speaks to its success among young readers. In a YA market where the biggest names are often books with male protagonists, seeing strong female-led books is critical. Amelia Westlake is a book that wouldn’t have been published a decade ago, let alone a bestseller, and its success can only help push more diverse stories into the mainstream.

However, this is also why it’s important to acknowledge some weaknesses among the strengths, especially in a book that tries to tackle the lack of diversity in our writing. As Kelly Roberts notes in her Conversation article, today’s YA heroine is “still very white and very upper middle class”, and this is an issue that will not be dispelled by books like Amelia Westlake.

Similarly, while parents will always try to choose the best school for their child, some parents have a lot more means to make that choice than others, a reality and privilege that Amelia Westlake does somewhat shy away from showing. The main characters given awareness of their privilege express it in deeply frustrating ways. Will lashes out at the Rosemead system, simultaneously hating it and still unable to recognise how significantly she is benefitting from it and her own privilege as the child of successful, upper-middle class parents. An exception to this is the character of Nat Nguyen, the impassioned editor of the Messenger, who works as a diverse voice among the largely white feminism of the novel. Nat’s reactions and growth throughout the book are effortless to read and feel deeply authentic, as she risks her future by publishing the AW comics and works to lift other voices up.

In her wake, Will’s characterisation as a state-school kid on a scholarship sits uncomfortably. Will doesn’t sound like the girls I went to school with, or like someone readers will recognise in their class. This is exacerbated by the depiction of a private school that sometimes comes across less as an Australian school than a re-purposed Downton Abbey with all of the attached classist undertones and distaste for the masses. With the occasional Aussie slang thrown in, this setting is captured in Beth’s line, “What’s the point of going to this school if we still have to mix with the povos?” While keeping an adaptable setting helps Amelia Westlake achieve the difficult nod of being picked up internationally, it also does a disservice to what could have been a critique of an Australia-specific private school culture, shielding it behind a global face. The book’s blurb also edges toward the cliff of misleading plot lines, branding the story as a “heist”. This leaves readers searching for the plot line they missed and overall, blurbs that promise things their book can’t deliver get confusion instead of praise.

But with that said, one thing is still true, and that is that we need to see more Australian YA like this. Erin Gough might not have hit every nail straight on the head, but Amelia Westlake is a funny, touching, and deeply meaningful novel, which doesn’t let queerness define the story of its characters. It also acknowledges the uncomfortable truth that young women need more powerful books like this that acknowledge the severity of the issues young women face. That know that in our current world, we can’t completely protect them – but that we can empower them to speak out. I really enjoyed reading this book, and I’ll barrack for every Australian queer girl story I can, especially the rebel girls. Maybe, with a few more of them, many of us would have felt less alone.

Other notes:

- My high school is now better known as Glennridge Secondary College by Aunty Donna, which is cooler than a professional footballer going there.

- WYS NERO stands for ‘Why You Should Not Eat Raw Onions’. My friend was politically ahead of her time.

- Check out other Golden Inky shortlisted titles here.

- If you’re keen to take in some more local queer content I recommend checking out Melbourne-based queer history podcast Queer as Fact.